Some mornings I wake to a message from my grandmother:

“Just came out of your beautiful lake. Couldn’t resist it in the stunning sunshine in harmony with Matawhaura. Much love from your haukāinga.”

I’ve just awoken to the rubbish truck emptying our bins and two crows whining on our rooftop. What a tease. Sometimes she’ll even send a photo of our glistening lake, and I feel my sigh in the morning mist on the horizon.

Matawhaura is the mountain that dips its toes into Lake Rotoiti, which feeds into Ruato Bay – the fern-fringed oasis at the end of my grandparents’ driveway. Most days she’ll brave the cold, my grandmother. My Koro (Grandad) less keen on the icy bite. He will stand on the shoreline and wait for his lover to return. I often stand torn, resisting the urge to disrupt the glassy surface – but there’s nothing like sliding into the fresh coolness. The water is like silk. Surrounded by mountains, there’s a lull in the breeze before the birds call, where everything is still yet calling you into its arms. Really sink into this image. I yield.

Here is my haukāinga, my true home.

Mai Maketū ki Tongariro.

Ko Te Arawa te waka.

Ko Rotorua te haukāinga.

From the shorelines of Maketū to the base of Mount Tongariro – this speaks to areas identified with the tribes of the Te Arawa canoe, the canoe my ancestors travelled here from Hawaiki. My whānau live in the geothermal landscape of Rotorua in the central North Island of Aotearoa. My work for New Breed “From the Horizon Thereafter” is a personal reflection on this land that I come from.

He ngāwhā, he hāora, he waiora. Boiling waters, breath of life, waters of wellness. The land itself breathing health and vitality into its people. Under the land, water flows from lake to lake (there are many lakes – “Which of your lakes would you like to swim in today, moko?” The great debacle when I return home for summer. Lake Tarawera is my favourite). Above the land, it erupts from the earth. Pōhutu is the largest geyser in the Southern Hemisphere. Through the soles of your feet you can feel the pressure building before it bursts upward, cascading steam and heat. More quietly, it boils in bubbling springs and pools – warm, soothing waters for the people. This resource, Waiariki, is a treasure and not taken for granted.

Whilst my Grandma swims lengths in our lakes, my Koro prefers to soak his skin and bones in the baths. Once holes dug in the ground, they have been part of his everyday life. People have always lived around the springs for their healing properties. There used to be many more until land was taken – building restrictions with no alternatives or consultations. They talk about the older people, when they were younger, going to enjoy a good soak, and the knowledge they held about which waters relieved different illnesses or injuries.

I come from, belong to, and will return to the land. I am its past, present, and future, and it is mine. My kinship traces back, past the human and divine, to Papatūānuku the earth mother. These ancestral ties are bound to the creation of land. Certain boundaries and areas help identify myself amongst iwi and hapū (tribes and sub-tribes) and plant me firmly. When I go home, we drive past this mountain and that lake and that rock, and Koro goes, “This is your Tūhourangi side,” and “That is your Ngāti Pikiao,” and so when they say “This morning we went for a walk in your redwoods forest,” or “We went for a swim this morning in your Ngāti Pikiao and Ngāti Rongomai lake of Rotoiti,” I feel equally spoilt and equally held – reassured of where I stand in the world, that I am a seed of Rangiātea, no matter how big or small the percentage of whatever blood I have.

“Your haukāinga awaits, and we’ll warm up your lovely lake to make it more swimmable in the meantime.”

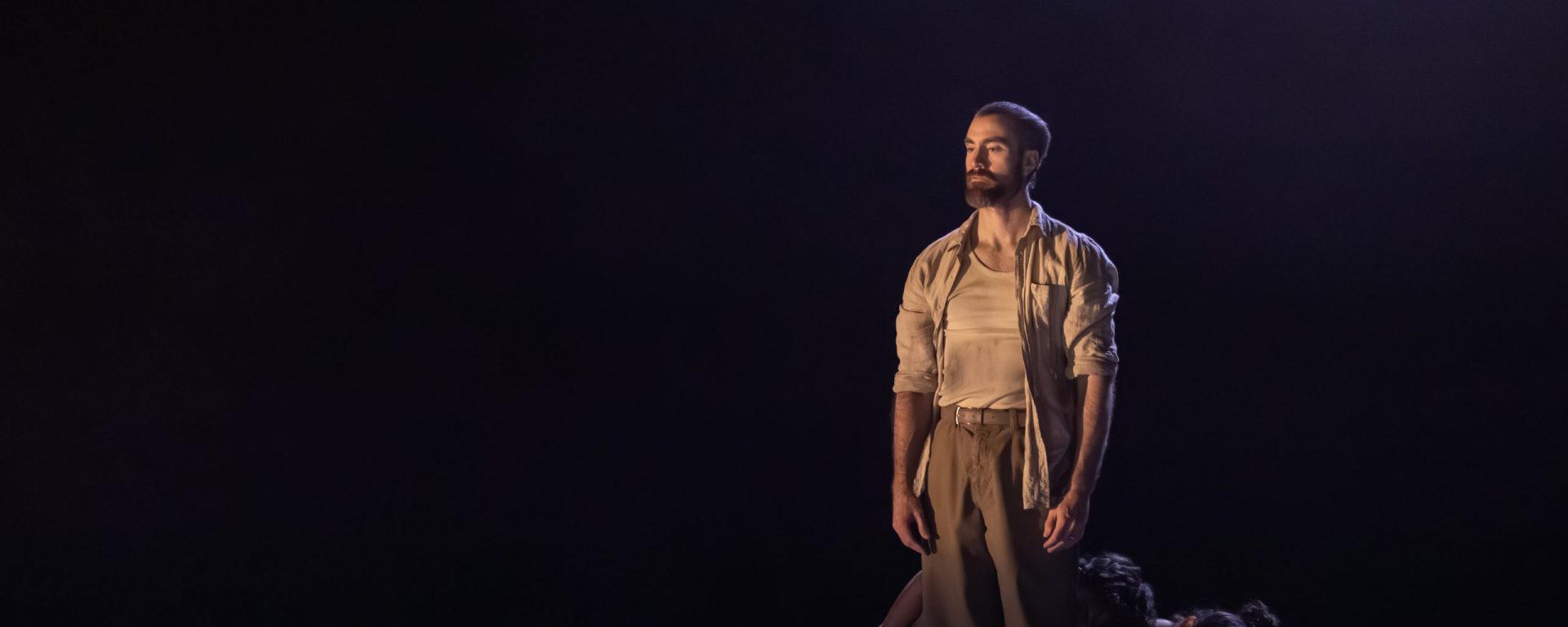

As the landscape changes, movement becomes a way of listening – a way of honouring what holds us and what endures, even when parts of a culture are asked to disappear quietly. “From the Horizon Thereafter” is a personal offering of what I carry from home: a quiet invitation to listen and be led by the land, a way to share story and offer an emotional connection to a living landscape. Through movement, the dancers trace a living memory of land, drifting between the natural world and the body – the land’s quiet exhale and its fleeting beauty. It grieves the spaces once tenderly walked upon, while honouring the delicacy of water flowing, the holding and the yielding, the tension between presence and loss.

Ngaere Jenkins’ new work from the horizon thereafter plays as Sydney Dance Company’s New Breed program, at Carriageworks from 3 – 13 December. Tickets are available here.