Sometimes, subtlety supersedes simplicity.

Taking the historiography of Australian cricket and shifting its focus back on to the forgotten Indigenous icons who shaped it in 1868, Ensemble Theatre’s season opener is ripe with emotion, wit, and reflection.

Notwithstanding issues of narrative pace and thematic expression.

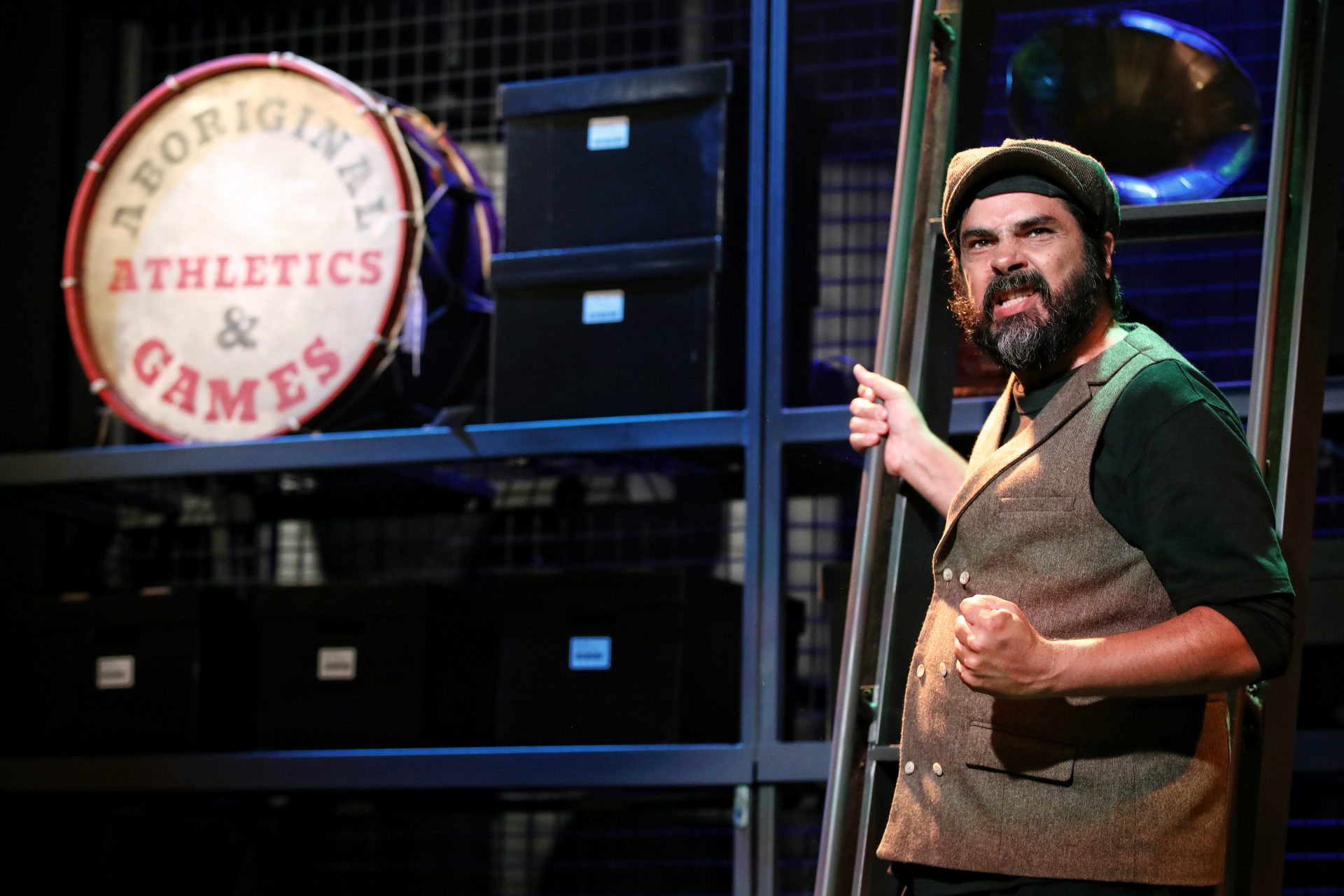

It’s not Wesley Enoch if it’s not as comedic as it is confronting, and the longtime director wastes no time in setting Black Cockatoo up as such. Luke Caroll immediately captures the audience’s attention as the fourth-wall-breaking Curator, introducing Johnny Mullagh and the first Australian cricket team to tour England by distributing aged but essential props (such as an 1860s-era watch and cricket cap) throughout the audience.

Deftly warming everyone to the show, he then makes the first of many exits. Bar occasional well-received returns to insert these props back on stage, explain parts of the story, or play a few minor roles, Carroll lets the dual narrative of Mullagh’s 1868 experiences and the actions of a modern-day Aboriginal protest group play out.

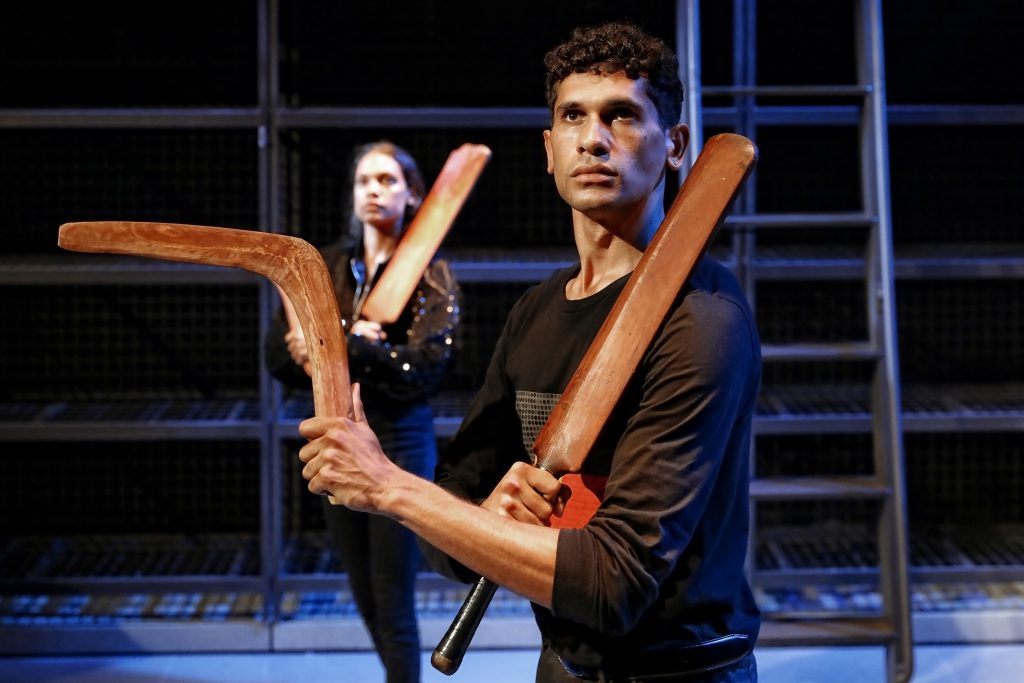

Aaron McGrath presents a spirited performance as Johnny Mullagh, capturing the Indigenous cricketer’s cheek and assertiveness whilst creating great chemistry with his slimy white captain Charles Lawrence (Colin Smith) and dynamic English interest Lady Bardwell (Chenoa Deemal). Though only telling half the play’s story, his at-times aphoristic dialogue is delivered with a rousing passion that uplifts those around him.

And uplift it does. Smith and Deemal, alongside Joseph Althouse and Dubs Yunupingu, comprise a cast that swings between Mullagh’s cricketing contemporaries and a 2020-era Aboriginal protest group. On their own, their performances are mixed; but together, they make for truly inimitable theatre.

Undoubtedly, Althouse and Yunupingu give the most contrasting performances. Whereas Althouse sings, moves, and speaks with scene-stealing strength (using the most comical English accent I’ve ever heard), Yunupingu’s rushed character transformation forces her to give a performance that jumps too boldly between anti-cricket pro-Instagram protestor to emboldened revolutionary without enough justification.

With the consistency of Smith and Deemal, however, it’s easy to find the play’s funeral for travelling cricketer King Cole to be one of the most well-directed and genuinely heartbreaking theatrical moments performed by the entire ensemble – regardless of these varied individual performances.

Unfortunately, it is after this scene that certain flaws become apparent. Geoffrey Atherden’s script utilises fast transitions and excessive explicitness to keep the play moving and accessible. The results of this – a string of jokes immediately after King Cole’s funeral and Yunupingu’s connection of her character’s arc with the play’s themes – undermine the audience’s intellect, leaving them with an adverse feeling at the performance’s end.

Ultimately, this play is to be commended for its depiction of a story that never gets told enough. The shortcomings of Atherden and Yunupingu are easily forgotten amongst the brilliance of Carroll, McGrath, Althouse and Enoch. Cricket fan or not, there is much to enjoy in Black Cockatoo‘s innings.