Come for the concept, stay for the art installation.

In the wake of the Helpmann Awards, Sydney Theatre Company has continued to revisit great texts of the past in its re-imagining of William Golding’s classic Lord of the Flies. Indeed, on face value Director Kip Williams has taken to this production the way an under-experienced, under-resourced schoolboy himself would; what first strikes the audience as they take their seats is the bare Roslyn Packer stage, the casually-dressed cast nonchalantly pacing around it, and the unremarkable upstage fluorescent lighting. They know there’s something sinister lurking beneath this thin veneer of calm, they just can’t see it yet.

Once they do, it’s unforgettable.

Where Williams’ show shines is its stagecraft, simplistic and complex simultaneously. The stripped-back nature of Elizabeth Gadsby’s set pieces, which include of a large tiered scaffold, boxes traditionally used to house stage lights and lighting materials, and unpainted timber chairs (among others) screams primality. The status the cast imbue on such meager set pieces – the scaffold becoming the deserted island’s mountain, chair legs becoming spears and such – acts as a strong visual conduit for the audience. It communicates that Golding’s characters are abandoned, free to make what they will of the world around them for better or worse. The joy of this set is that the theatrical veil is never lifted; rarely is the audience’s disbelief suspended, exposing them to the play’s savagery more intensely.

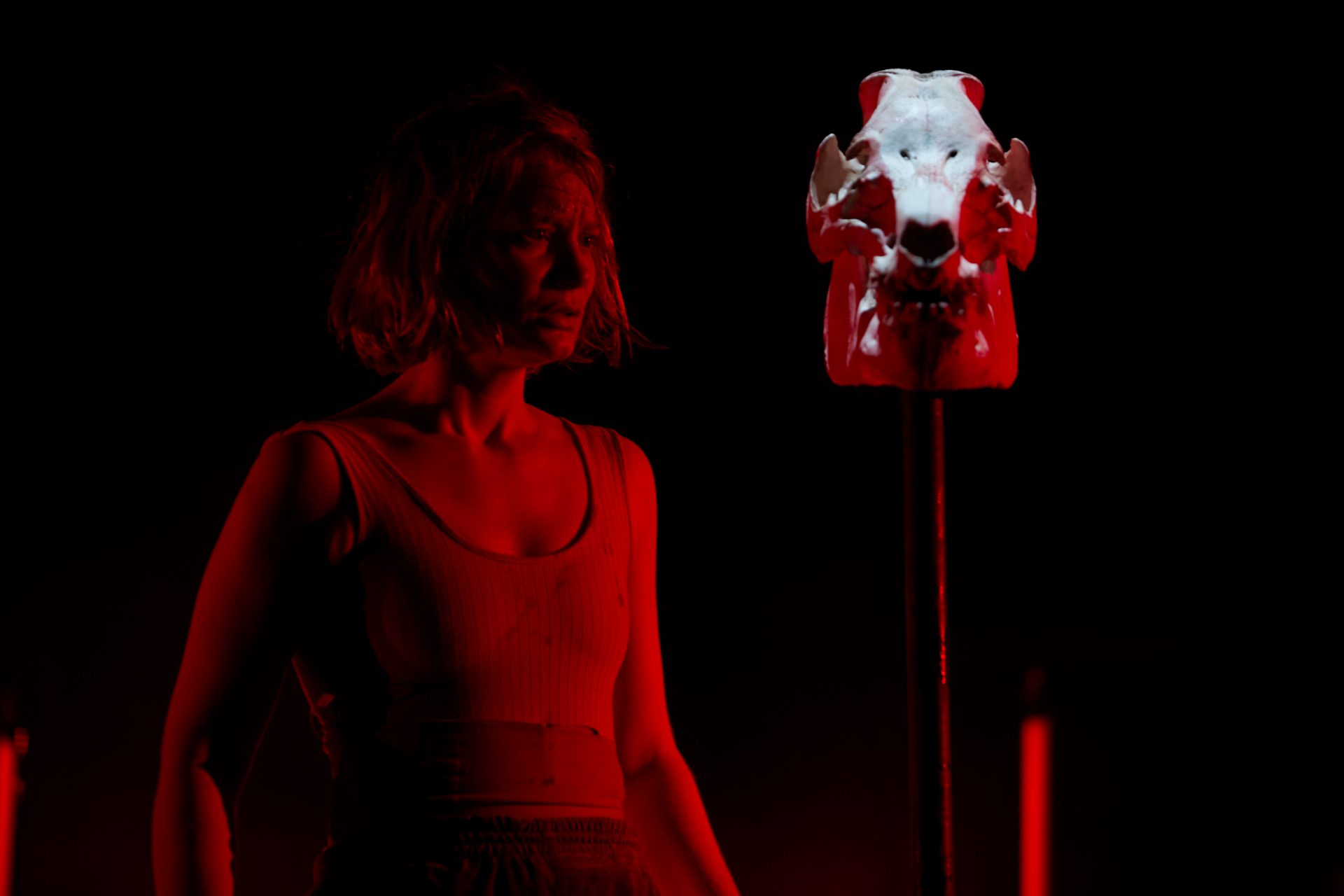

It is, however, Alexander Berlage’s lighting design that gives Lord of the Flies its ‘wow’ factor. Williams has taken an often static element of theatre and not just improved on it within this show, but made it an essential element to the performance. Including the aforementioned upstage fluorescent lighting, those on a traditional truss, and most notably LEDs held on individually-movable cables often organised into neat rows, Berlage’s use of colour – and occasional removal of lighting entirely – is immensely striking, particularly when the stage is sparsely decorated in ambient crimson. Williams’ incorporation of these rows of lights into the set, which form a physical maze for the actors as they are lowered to hip-level or become disordered as different lights in different rows are operated to shoot off and out of their pristine order, is the show’s ultimate strength. As said previously, simple and complex simultaneously.

Such duality is also present in the cast performances. The 12-strong ensemble, 9 of whom make their STC debut in this production, deliver an incredible chorus performance. There is little to fault in terms of their energy, savagery, and devotion to the easily-influenced mob-mentality mindset that almost every privately-educated schoolboy of a young age has. The moments of goosebumps after the play’s more animalistic scenes are too numerous for this writer to recall, and their stunned silence after the more animalistic of their actions creates an aura of guilt so palpable it’s unbearably pleasurable.

On an individual level, the cast are a bit more divided. Audiences will take particularly well to Mia Wasikowska as Ralph; her characterisation and vocal skills match the demands of the leading character almost perfectly, allowing her to meet Williams’ hopes of moving the text beyond just a boys-only club. Rahel Romahn is a wonderful Piggy, capturing the annoying-but-necessary essence of the character’s way of thinking and the only actor to draw out a variety of responses from the audience. His final monologue must rank among the show’s most memorable. Joseph Althouse as Simon has a lovely stage presence, though his character’s much-revered demonstrations of morality are somewhat lost amongst the visual spectacle of the set or the dialogue of other characters. Mark Paguio and Eliza Scanlen as the younger-aged Sam and Eric round out Ralph’s gang with an under-appreciated display of youthful innocence and archetypal sibling banter.

Within Jack’s (Contessa Treffone’s) rival gang, the bigger draw is those around the chief. Treffone, cast in an antagonistic role that demands both fear and naivety, only succeeds at the latter. Her Jack is one that is distinctly schoolboy, with flashes of humanity both physically and vocally doing well to establish this. Yet, as the play progresses, the audience never fears her; the element of raw aggression that makes this terrifyingly unpredictable character who they are is not quite displayed. Her gang do what they can to help her – Daniel Monks as Roger and Yerin Ha as Maurice notable supporting stand-outs in this regard with respect to their energy – but they actually go one step further and outshine their leader. Noting the production’s play on gender, this writer is nonetheless of the opinion that Justin Amankwah, who plays the under-utilised but always well-depicted Henry, would be an ideal Jack; it’s clear he has the intensity and ability to pull off such a role, and it would be interesting to see his chemistry with Wasikowska’s Ralph.

Ultimately, even with the mixed performances, this is a great production. The technical elements included in the show are unmatched anywhere else, making for an experience that is genuinely memorable for many of the right reasons. It’s bound to pick up multiple nominations across the board, and as such is no less than mandatory viewing for lovers of any art form.