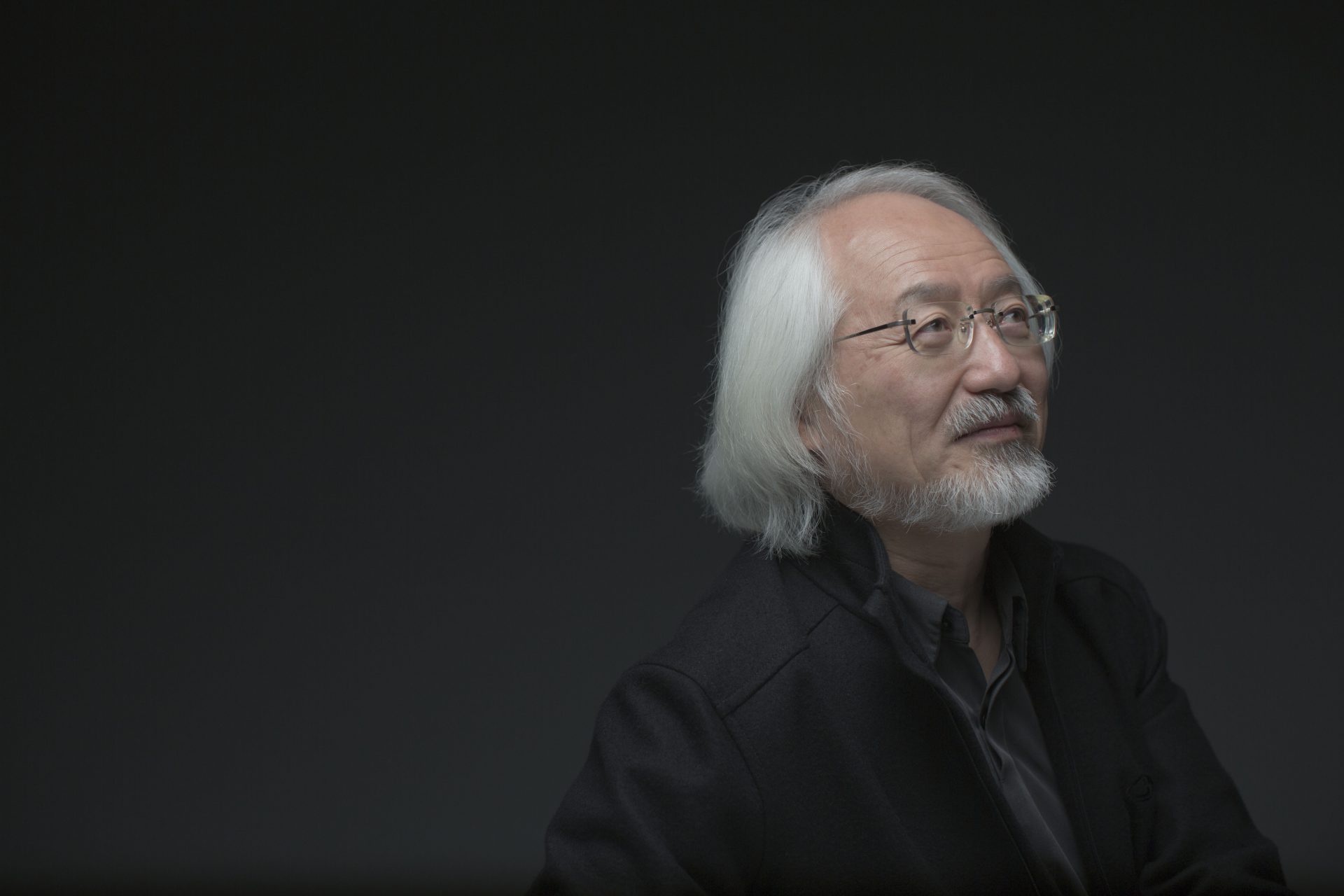

This month, Sydney Opera House was graced with the presence of revered musician and interpreter of classical music, Masaaki Suzuki, conducting the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

This concert featured a turn away from his Baroque repertoire, focusing on three of Mozart’s works – the Overture to Don Giovanni, the Linz Symphony, and the Great Mass in C Minor.

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra burst out with that distinctive D minor cadence that opens the overture to Mozart’s famous Don Giovanni. Here is music that demands attention. The mysterious scales that follow were played to great effect by Carolyn Harris on flute, who heightened the impression of a crescendo by exaggerating the softness of the repeated high notes. Then follow the light-hearted fancies in D major which are so typical of Mozart and in which the strings section immediately finds itself at home.

Next was Mozart’s Symphony No 36 in C major, dubbed the ‘Linz Symphony’, which he had written in four days. The allegro spiritoso is replete with dramatic build-ups, shimmering tremolos and exhilarating turns, which the strings section despatched with ease and as though with the casual flick of a wrist. Then comes a wistful chromatic section on the oboes, which catches the audience almost by surprise, and a series of scales on violin and viola redolent of the Don Giovanni overture that came before.

The highly lyrical poco adagio that follows is reminiscent of the siciliano form of which Baroque composers were so enamoured. This is charming, galant music though, curiously, it features horns and timpani.

In the menuetto, Masaaki Suzuki made the phrasing short and punchy. We then have the interposition of an obligatory trio where the oboe Diana Doherty takes the lead on oboe. The Presto follows in rapid succession, and rapid is here le mot du jour as Mozart directed the orchestral forces he had at his fingertips to ‘play as fast as possible’. So we have passages on the violins that leap upwards and frenzied passages that meander up and down at breakneck speed. The effect is exhilarating.

After a short interval came Mozart’s Great Mass in C minor. The motif of the Kyrie is a plaintive chromatic fall in which both instruments and choir participate. The Kyrie is true to form – an impassioned call to divinity for mercy. There is a slight change in character with a more optimistic cadence on violin that introduces Sarah Macliver elegantly singing the ‘Christe eleison’, who delves to the depths of the soprano range and reaches upwards to the highest in the space of a breath.

The contrast in the Gloria is stark. Suzuki realised this to spectacular effect, with a sprightly tempo and by giving prominence to resounding horns. The choir breaks out into a quaint, rather light, fugue, and the articulation was good throughout. The uplifting mood of the Laudamus te recalls that of the same verse in Bach’s Mass in B minor. But Mozart gives a much more florid setting here, with coloratura that is more familiar in the opera halls of Vienna. Rachelle Durkin did well in the tricky passages here – which traversed the extremities of the soprano vocal range in the space of a few bars. The instrumental introduction by the orchestra was very elegant. We have yet another contrast with the foreboding Gratias, where the choir shone.

The Domine Deus is set as a duet. Macliver and Durkin cut through the busyness of this aria with clarity. The Qui tollis is similar to the build-up effect in Bach’s Qui tollis and one gets the impression throughout of the influence of the Baroque masters – Bach and Handel – throughout his composition. The choir displays great dynamic control here. A highlight was Macliver’s performance in the solo soprano aria, Et incarnatus est, which gave the effect of a dialogue between soprano and wind. The Mass was rounded off, fittingly, with a rousing ‘Osanna in excelsis’.