A profound display of colonialism, nationhood, and retaliation.

Picnic at Hanging Rock, an adaption of Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel produced by Sydney Theatre Company, proves why this tale has remained in Australia’s consciousness for over 50 years. Dissecting the brutal takeover of Indigenous land and exploring its horrific consequences on the native people, while also offering a terrifying glimpse into a situation where the land fights back, the production is technically superb, masterfully crafted, and deeply resonant

This adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock, written by Tom Wright and directed by Ian Michael, has the same plot as its inspiration. On Valentine’s Day in 1900, four students of Appleyard College – Miranda, Marion, Irma and Edith – depart their posh private school for a picnic at Hanging Rock in Victoria’s countryside. The rock is the site of an extinct volcano and overlooks lush creeks, dense bush, and houses venomous snakes and lizards. Accompanying them are teachers Miss McCraw and Mademoiselle de Poitiers. Young English traveller Michael Fitzhubert and his friend Albert are also nearby. Back at Appleyard College are student Sara, teacher Mrs Lumley, and headmistress Mrs Appleyard. The group’s mysterious disappearance during their picnic causes an investigation that shakes all involved.

Wright’s script progresses the plot quickly while letting the play’s conceptual themes linger. The opening scene is performed at deliberate pace, with the five-performer cast rapidly reciting their dialogue so that Wright’s script can swiftly set up the characters, story, and setting. This helps to establish the tension as the girls venture into Hanging Rock. The script then noticeably slows down as their disappearance is investigated. The dread of what these proper English girls have suffered in the Australian land they attempt to dominate is considered in great detail. The dismissal of Australia as a backwards country, and Ms Appleyard’s slaver-esque treatment of Sara, separated from her family and experiencing significant emotional trauma, occupies several scenes. And the ethereal, otherworldly nature of Hanging Rock, which consumes more English characters the longer the play continues, is revealed. Though the ending feels slightly abrupt, these all present the colonial ignorance Lindsay’s novel embodied.

The cast adopt multiple roles and so are simply credited by their first names. Contessa Treffone plays one of the quartet and Michael well, particularly the latter who features towards the middle-end of the play. She showcases his naïvety and good intentions but overall ignorance strongly. Contrastingly, Lorinda May Merrypor primarily portrays Edith and Mademoiselle de Poitiers and is particularly strong as the former. The audience develops their fear of Hanging Rock thanks to her convincing performance. Olivia De Jonge plays Miss McCraw and Mrs Appleyard, and though her McCraw is devilishly good, her movement in a startling scene, writhing under a red light, is powerful. Masego Pitso, who primarily plays Sara, is stunning. She portrays Sara’s trauma viscerally, with her jerky and shaky movement uncomfortable to watch but clearly indicative of the immense pain her character is in. Her vocal performance is just as memorable, whether she is performing her trance-like dialogue, cackling with laughter, or groaning in pain.

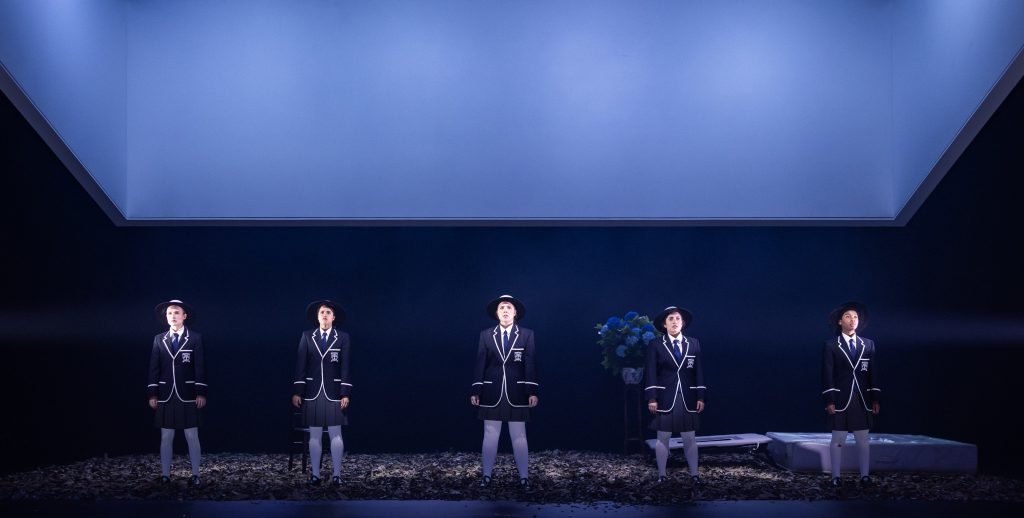

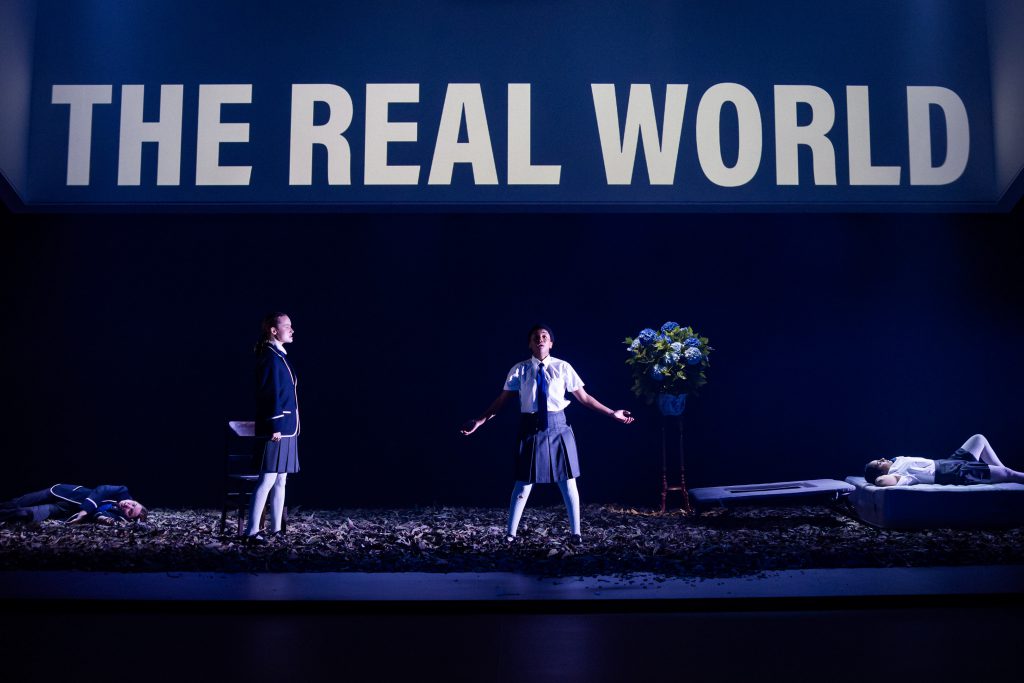

Michael’s direction takes this to another level. His set, courtesy Designer Elizabeth Gadsby, is stark and mysterious. It features a small centre stage space covered with dried leaves and bark, as if to draw attention to the fact that the soul of Australia lies in its land: it is constantly staring us in the face but we rarely notice it. Hovering above, is an open cube-like monolith, looming over the play’s actions. Though both indicate the Hanging Rock landscape, the monolith is especially notable. Words are occasionally projected onto it, always in complete silence and often while the stage is dark. It is unsettling in a mysterious, indescribable way.

Michael’s use of smoke and sound, courtesy Gadsby and Lighting Designer Trent Suidgeest, add to this air of mystery. Suidgest’s lighting in particular is snappy, with sudden flashes and intense red hues creating tension, intrigue and (at times) intimidation. Sound design courtesy Composer & Sound Designer James Brown supports the on stage action nicely, bar a singular bizarre inclusion of house-style music during a similarly bizarre dance sequence.

Ultimately, this adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock is immensely thought provoking. It takes the ideas of Lindsay’s novel and cleverly brings them to the stage, making use of everything the medium offers. Its inspiration has lasted for half a century, and this will prolong its legacy even further.