Passion in July.

Any performance of Bach’s St John Passion is a feat. It is not quite Bach’s Mass in B minor – which was meant to be a grand “study piece” summing up the best of Bach’s devotional music. Nor is it his St Matthew Passion – which is a bit showier, and more remote in tone, with long, ornate, drama-sapping arias. Bach’s St John Passion is the more intimate Passion, and presents a welcome challenge for the Willoughby Symphony Choir.

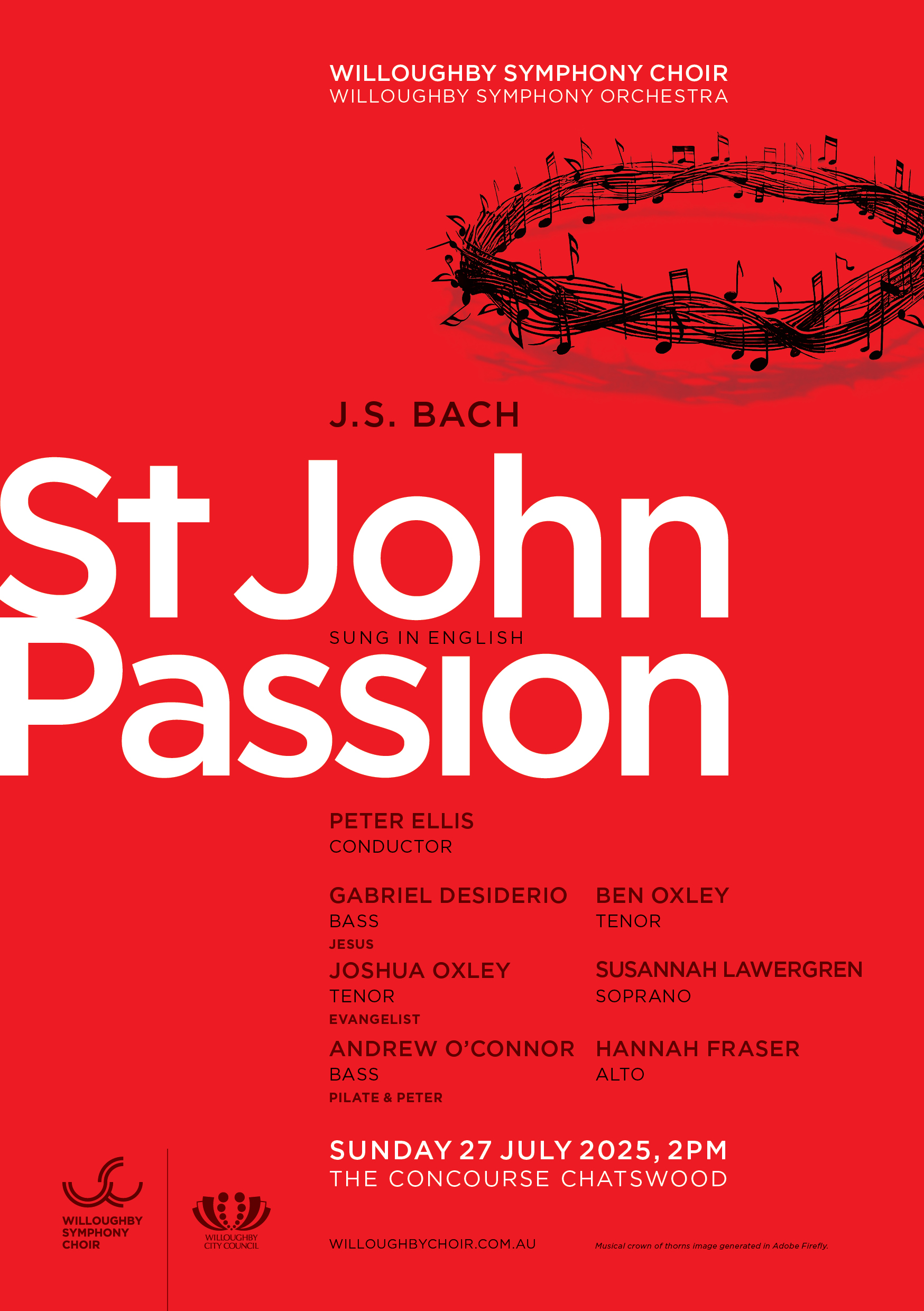

Conductor Peter Ellis led the sheer blizzard that is the opening “Herr unser Herrscher”, with oboes pitted against one another throughout. But this time it was not “Herr unser Herrscher” but “Hail, Lord and Master”. This Passion was sung in English, and the translator should be commended for preserving the scansion and making the libretto even more poetic than Picander did.

The double bass and the cellos stood out in this opening, but there were some slips in timing in the choir – which is only to be expected as the counterpoint thickens in the middle of the chorus.

Characterisation is particularly important in a story like the Passion. The evangelist exhorts. Jesus declaims. Peter reflects.

In Joshua Oxley we have a superlative evangelist. His performance is about as exhortatory as you can get. Clear, impassioned and confident, it is as though he is lecturing, protruding angularly, from the pulpit. That he did, in a recent performance of the St John Passion down the road in St Thomas’ Anglican Church North Sydney in Easter earlier this year.

Hannah Fraser was our first soloist, singing the first aria – “Von den stricken”, or “From the bondage of iniquity”. Again, the cellists were clearest here, with body given by Joshua Reynolds on bassoon, but the entire conceit centres on the tension between the oboists (as with the opening chorus) to depict the tightening bonds of sin.

Susannah Lawergren followed shortly after with “Ich folge dir gleichfalls”, or “I follow Thee gladly”. As Isabelle Ironside and Lucie Benz on flute show us, this is joyful music. It is a pastorale without the tempo. It is markedly like the “Wir eilen mit schwachen, doch emsigen Schritten” from BWV 78, only lighter. That is just as well. Lawergren’s voice is distinctly light. She left the audience in awe in the closing aria, “O hear, melt in weeping” (“Zerfliesse”).

All this is punctuated with a dramatic dialogue between the Evangelist and Andrew O’Connor as Peter. O’Connor shone in the difficult “Haste, haste” aria.

Gabriel Desiderio equally made an effective bass interlocutor in the dramatic recitatives. Remarkably, he performed equally well at an intensive Orchestral Mass featuring Gabrielli’s works in St James’ King St, only two hours before this performance!

The Evangelist foreshadows Peter’s lament with a tortuous melisma on “he…wept bitterly” (originally “weinete bitterlich”). It was executed with much pathos, and Oxley traversed the entire dramatic range with one adverb.

Benjamin Oxley performed the tenor aria, “Ah, my soul” (originally “Ach mein Sinn”). It is sometimes played so fast it gives the impression of a buccaneer’s chantey. Not here. Ellis directed a measured pace, but Oxley’s strong pleading tone lost none of the urgency.

It is clear the Willoughby Symphony Choir had worked on its diction. The chorale that closes the first Teil opens with a violent plosive. But by far the most violent chorale is “Christ, whose life was as the light” (originally “Christus, der uns selig macht”), which opens the second part with a bang. None of the “macht” was lost in translation. It is almost devastating in its bleak, modal, simplicity. Ellis capitalised on this by striking in media res, immediately after a long interval.

The second part is by far the busiest. The dramatic pace picks up. The chorus changes character from the Greek chorus commenting on the scene to the heckling mob. They taunt “malefactor, malefactor” with stabbing staccato. They emphasise that Barabbas was a “ROBBER”. But the audience is denied the calm reprieve of the Erwage aria. It was an aria well suited to either of the Oxleys. But it was nowhere to be heard.

Bach had a love for fractals. When the text says “law”, “die alte bund” or “ein gestez”, we get a canon (canon being Latin for law). The counterpoint at times is so close it is almost canonic. But that meant some slips in timing in the chorus.

This performance showed that a performance of Bach’s St John Passion is never out of time, even in July.