PANDEMONIUM, the latest exhibition of works by acclaimed photographer Toby Burrows, labels itself as ‘a photographic response to the pandemic’. Running at Alexandria’s SUNSTUDIOS, the almost 30 pieces on display collectively live up to this artistic vision.

Toby Burrows is known for his portraiture work, and that’s what viewers are treated to in PANDEMONIUM. The exhibition is mostly comprised of these portraits, which range from famous faces like Tim Minchin to more everyday people-you-see-on-the-street subjects. Yet, in a deviation from his clean-cut photography style, most display pieces have been distressed and aged; the work appears crumpled, like paper that has been scrunched up and flattened out again. In many ways, it’s a fitting ode to how many of us have felt over the past two years.

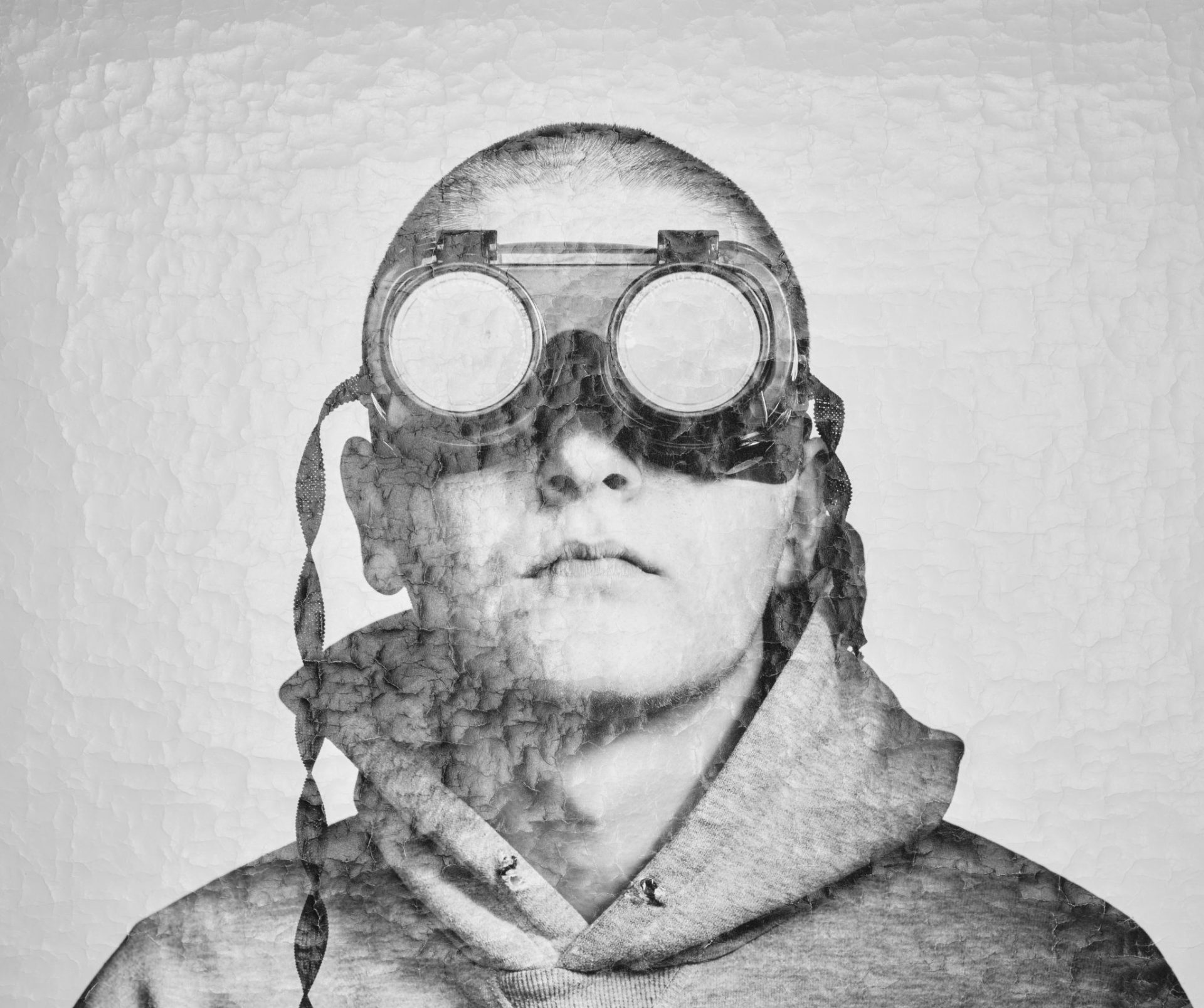

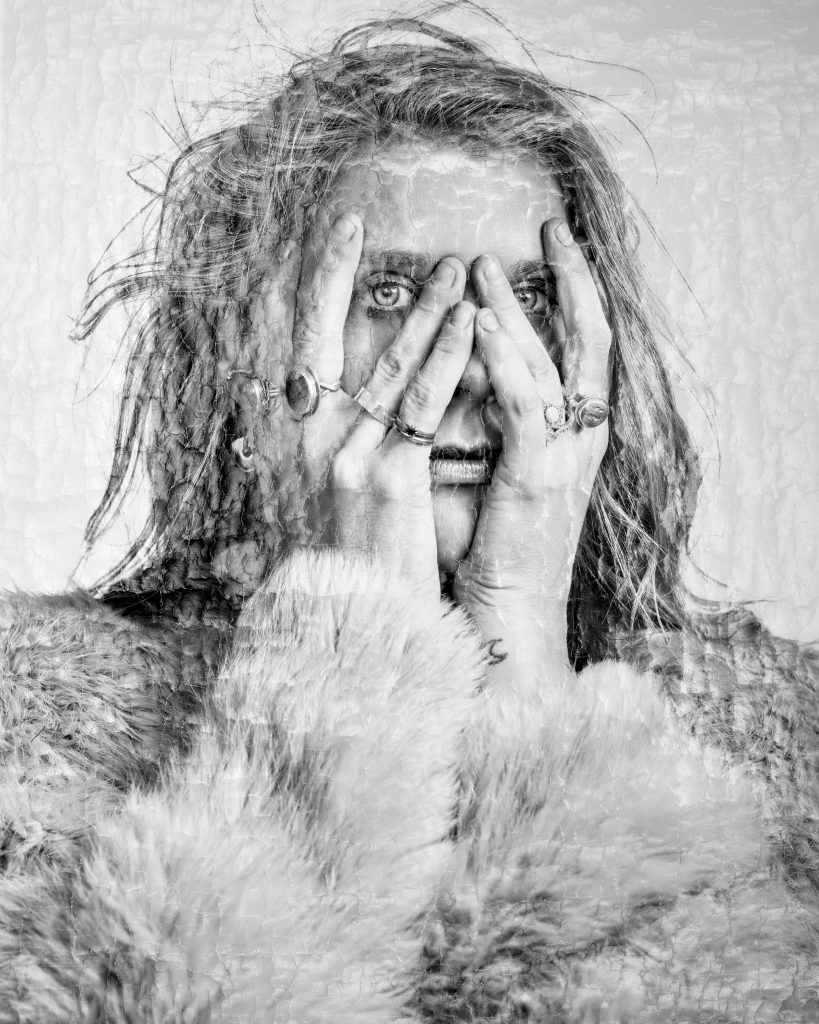

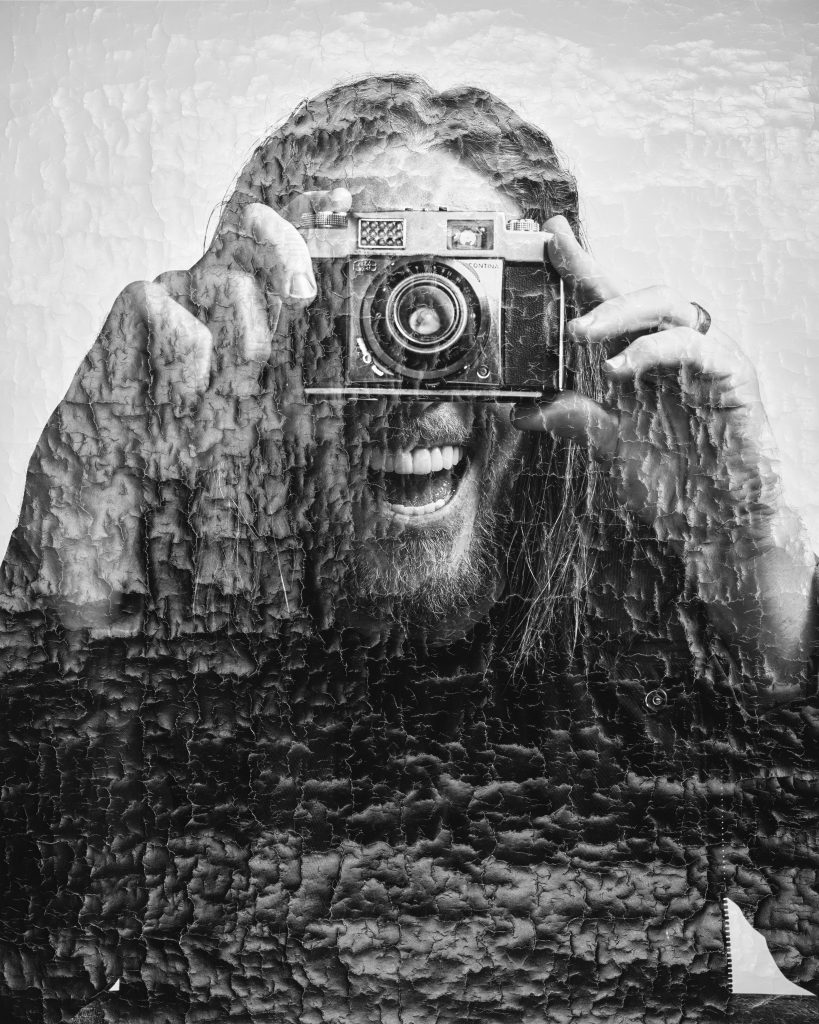

The joy of PANDEMONIUM is when this distress is maximised. In the exhibition, each work is distressed to a different extent. Some portraits are noticeably more distressed, and from them we see a unity between subject matter and composition that brings out the best of both.

Ink – a portrait of Simon Harsent, for example, is a stunning display of the contemporary human psyche. Harsent presents an authentic anguish, but since half of his face is hidden, an audience’s ability to connect with this anguish is minimised. Yet, thanks to the distress Burrow has applied to this work, we are instead exposed to a more implicit suffering; one which feels more intimate, more real. Each crinkle draws us closer to Harsent’s mentality, revealing his inner turmoil in a way he has tried so hard to avoid.

Through similar means, there is a fun playfulness to PANDEMONIUM‘s other works. Analogue – a portrait of Tim Minchin expresses this brilliantly. Though it is just as (if not more) distressed than Ink, and again features a subject whose face is largely hidden, it exudes an incredible warmth. A relaxing crescendo of light works to counteract the potentially harsh impact of the piece’s distress, with its ironic subject matter contributing to an overall sense of lightheartedness. In doing so, Analogue becomes akin to rediscovering a fond memory, packing a contrasting (but just as emotional) punch to Harsent.

Of course, these are just two of many examples present in the show. Ink is wonderfully complemented by works like Deconstruct – a portrait of Jez and Ceremony – a portrait of Women. Analogue fits well with works like Lyrical – a portrait of Ali Nasseri. This type of diversity is PANDEMONIUM‘s ultimate strength, exposing audiences to the souls of Burrow‘s various subjects.

However, such exposure relies on two factors: the distress/age being maximised, and the distress/age being equitable to the work’s original impact. If either one of these are in issue, the exposure is correspondingly limited. The extent to which this shortcoming is realised depends on the viewer, but for this writer, it was more readily recognised in non-portrait-based works such as Fable and Renaissance.

Nevertheless, there is a lot to take from PANDEMONIUM. By physically degrading his old work, Burrows has breathed new life into them, giving audiences a delightful insight into humanity during the pandemic. No matter your artistic disposition, this is an exhibition that should not be missed.

PANDEMONIUM runs at SUNSTUDIOS until 27 August.