Simple. Heartfelt. Meaningful.

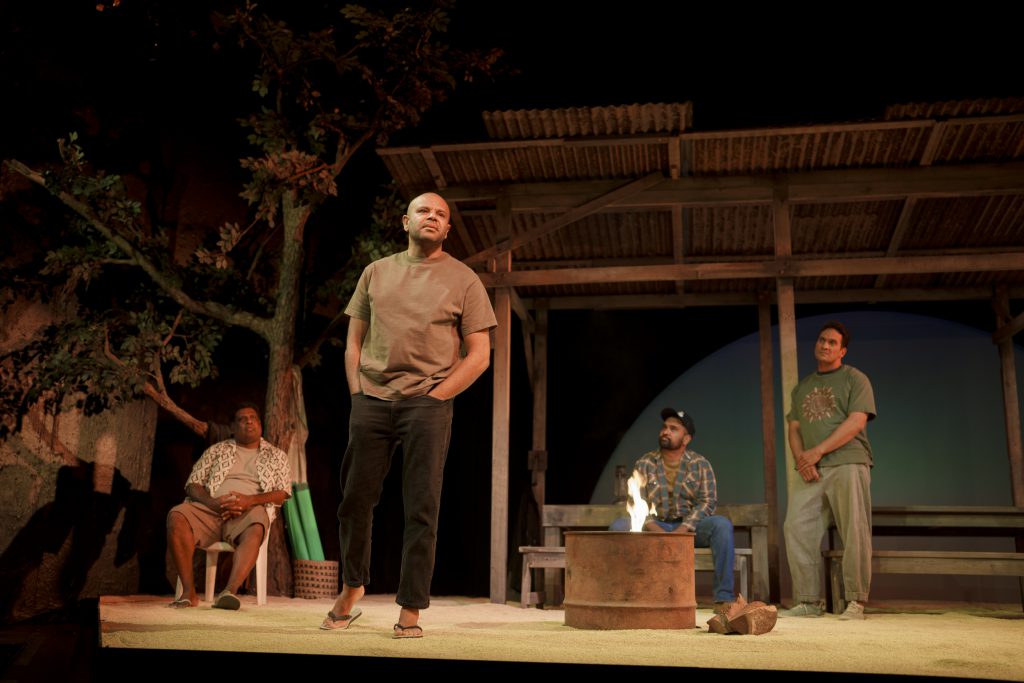

Dear Son, playing at Belvoir St Theatre as part of the 2026 Sydney Festival, presents a unique display of quiet courage and father-son relationships. Produced by Queensland Theatre Company and State Theatre Company South Australia, it resists excess in favour of a gentler experience. It does not strive to dazzle; instead, it invites the audience into a space of reflection, listening and care.

Dear Son explores notions of love, trauma, silence and expectation. Based on the book by Thomas Mayo and adapted by John Harvey and Isaac Dandric (who also directs), the play concerns five First Nations fathers writing letters to their sons. Yet it goes much deeper, looking into the weight of toxic masculinity, cultural obligation, emotional restraint and the injustices suffered by First Nations Australians. Conversations unfold in rhythms – hesitant, elliptical, humorous, sometimes indirect – to ground the play in a recognisable emotional truth.

The cast give solid performances, sharing a commitment to honesty and emotional precision. Each actor brings a sense of care to their role, allowing the characters to exist as complex, imperfect people rather than symbolic figures. Particularly strong are the moments of stillness – a pause just slightly over-held, a line delivered without emphasis – where the emotional stakes emerge most clearly. Yet the cast also lean in to the script’s more humorous elements, from stories of outback road trips gone wrong to the idolisation of the footy. Of particular note are Tibian Wyles for his comic ability, Waangenga Blanco for his movement skills, Jimi Bani for an eye-opening monologue about the Indigenous people of Hobart, the Palawa, and Dandric returning to the stage after 13 years – stepping in last-minute due to cast illness.

That said, Dear Son takes its time establishing its characters and thematic concerns. Early scenes arrive and depart without always making clear how they are accumulating toward something larger. Though this sense of meandering is not without purpose, the effect is nonetheless testing. Ambiguity can be a powerful tool, but here it occasionally slides into a lack of clarity, where one wishes for a firmer dramaturgical hand, or at least clearer signposting. Fortunately, when the play does finally begin to cohere, it does so with considerable grace.

Ultimately, Dear Son is sincere and heartfelt, rewarding attentiveness and empathy. Its simplicity is a deliberate choice, which allows space for nuance and emotional complexity. While its initial slow burn prevents it from fully realising its potential, the authenticity of the writing and the care evident in the performances ensure it lingers long after the final moment. This is a play that speaks softly, sometimes too softly, but when it finds its voice, it speaks with real feeling.