Last year, Sydney audiences were treated to a performance of Purcell’s Dido & Aeneas, directed by Erin Helyard of Pinchgut Opera fame. Last night, the same conductor picked up the baton for a performance of an Opera Queensland production of the same opera, only this time in the Joan Sutherland Theatre and in conjunction with acrobats from Circa.

The beginning was not the beginning. In the fine tradition of Renaissance and early Baroque drammi per musica which sought to invoke something of the Classical world, the conceit began with a Prologue. The Prologue, usually featuring allegorical characters, this time featured interpretative dances and acrobatics. The original conductor, Benjamin Bayl, neatly wove through some of Purcell’s other works, such as his fantasias and sonatas in three parts, as well as the solo “The fatal hour comes on apace” – which served as a neat premonition for what was to come.

The opening sinfonia showed Purcell’s liking for jarring chromatic pivots – a style developed in early English viol music. They were so popular they became known on the Continent as the “English cadence”.

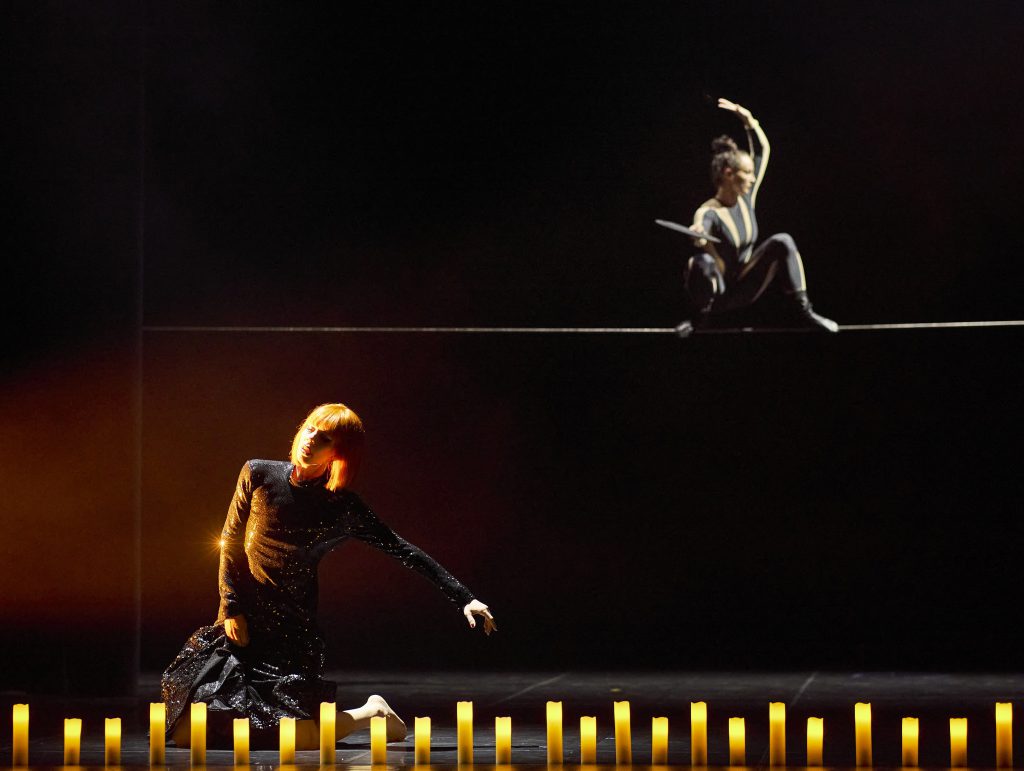

In the spirited B-section of the overture, we see Dido caught in the metaphorical threads of time, which are braided by a half-dozen nimble acrobats. That was one of the best uses of acrobatics in this performance.

Purcell sought to imitate the forms of ancient Greek drama – powerful rhetorical flourishes, simple music serving the words, and a prominent chorus which interposes suddenly to comment on the scene that has just unfolded. So immediately after we hear from a love-struck Dido – sung by Anna Dowsley, a Pinchgut favourite who delivered a strong performance from the outset – she is cut off and the chorus assumes centre-stage. This is theatre stripped to its essence.

It took some time for Jane Ede as Belinda to assume the vocal clarity required of that role, but it picked up resolutely in the field scene. Dowsley could stretch a word and make it traverse the whole dynamic range, and Nicholas Jones as Aeneas had a voice that was at once robust and soft, in a way redolent of Andrew Goodwin’s. The sorceresses – Angela Hogan and Keara Donohoe – performed convincingly and did well at pulling off the vocal equivalent of playing too close to the bridge.

Discerning listeners would have noticed another element of the genius of Bayl’s design, in Erin Helyard’s capable hands. Before the drama condescends into the depths of the sorceress’ lair, Dido sings the famous “Cold Song” from Purcell’s King Arthur. She sings legato, with the chorus giving the famous staccato effect with delicious harmonisations. (It was a clever way for Dowsley to change personas, from Carthaginian Queen to scheming sorceress.) And before Dido resolves to die, we hear the orchestra play Purcell’s “Funeral March for Queen Mary”. In that mini-prologue to the final Act, one acrobat lies dead and is solemnly lifted, one by one, almost to the theatre’s ceiling. I was also reliably informed by a discerning colleague that some of the lyrics splayed on the surtitles were from “Total Eclipse of the Heart”.

Of course, none of those features in the original. But they show why Helyard has assumed the role of consummate master of Baroque performance in this country. Yet it was a shame that there was no chaconne for the Cupid scene – a simple set of figured bass notation which leaves a world open for keen improvisors.

In some of the intermezzi, which must have originally been masque balls or such dances as gavottes or gigues, we hear incidental music from Matthew Locke’s earlier setting of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. That is fitting. Music and dance were indispensable parts of Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre, and The Tempest was the high water-mark of that style. For all this, one wonders whether this production could have made better use of the acrobatics. For one, the choreography was too vertical and often static. Dance music requires more movement. Greater use could have been made especially in the spectacle Sian Sharp conjures as Second Lady when she narrates Acteon’s fate beside the fountain – a vignette which was practically begging for some form of interpretive dance or apologue.

There were other delightful effects, like the use of Baroque drums, to impress many of the more dramatic scenes with the effect of a tombeau. The aelophon’s winds and screeching sound effects were interrupted in part by injudicious clapping.

As is well known, Dido’s lament is based on a falling chromatic fourth. That simple but devastating motif was spelled out first on the harpsichord, then on lute and finally on cello, before Dowsley gave it her all. It is tempting for sopranos, caught in the moment, to screech when they ascend to the higher “Remember me”, but Dowsley mercifully spared the audience of that. Control and lyricism were the hallmarks of her performance throughout.

The closing coda was a chorus in which the singers surrounded the audience, imploring us, in a resigned tone, to remember Dido and her story. It will be difficult not to.