A classic 1920s crime tale of heroes and damsels in distress that didn’t quite save the night for the audience.

Despite a plotline that often seemed arbitrary and difficult to follow, a sophisticated direction and noteworthy performances resulted in a show that exemplifies the potential of independent theatre in Sydney.

Set in late 1910s Britain, Liz Hobart’s Betty Breaks Out follows the misleading kidnapping of leading lady Betty (Annie Stafford) and film hero Fred (Tommy Misa). From the beginning of the play, audiences could idealistically assume the play is driven by a political message against toxic masculinity and a woman’s place in a man’s world – however, this was lost in an often confusing narrative of false kidnapping and hidden treasure.

Stafford steals the show by creating a character that is often endearing, resulting in a genuine connection with the audience. Her characterisation, strong stage presence, and convincing British accent helped overcome the lack of narrative consistency in Hobart’s dialogue. The strength of Stafford’s craft lies more in her ability to bring Betty’s comedic moments to life, with her best lines more humorous in nature.

On the other hand, Misa’s characterization wasn’t as strong as his castmate, with both moments of humour and tension not quite getting their desired audience response. Fred is a challenging character, with an obvious-yet-very-late-to-the-table reveal of motivations. The anti-hero status Misa tried to reach wasn’t quite solidified as the character often seemed shallow, with a significantly less amount of performance time dedicated to Misa’s character development when compared to his castmate.

Nevertheless, due respect must be given to director Ellen Wiltshire for her clever use of the KXT space. Creating a warm and inviting theatre that suited the narrative of the play, the constant rearranging of and diverse interaction with various set pieces enabled a linear and easy-to-follow flow of time. The often abstract separation between characters resulted in elevated staging decisions that enhance the interactions between the trapped duo.

Effective sound design and original music from Alexander Lee-Rekers, with lyrics by Hobart, added a refreshing layer and dynamic to the show, enhancing the moments of tension as well as providing enjoyable moments of musical theatrics.

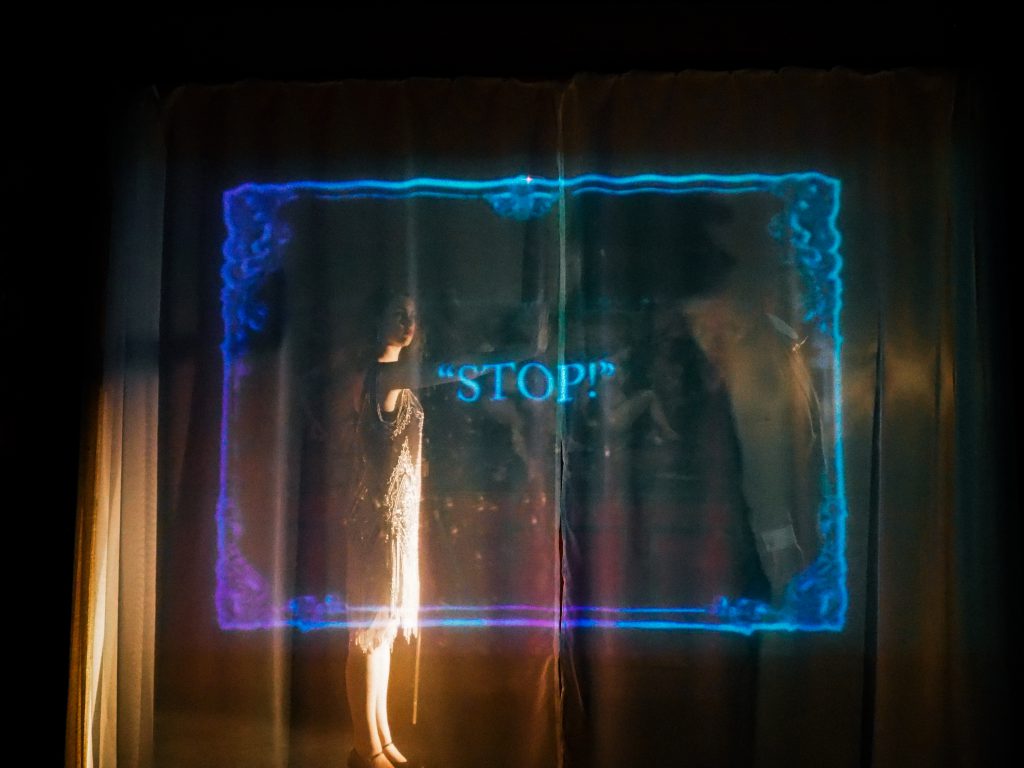

Furthermore, the interesting creation of 1920s style silent films through projections and lighting (props to Production Designer Isabella Andronos and Lighting Designer Sophie Pekbilimli) added another dimension to the play, placing the narrative in its time. The moments of “silent film”, creating a striking but ambitious motif that aimed to highlight the overarching themes of the play, were unfortunately lost in the confusion of the storyline.

Additionally, the continuous intentional breaking of character (with actors mumbling their next line during scene transitions and breaking into out of character mid-conversation) did not seem to align with the storyline or themes of the play.

Overall, those involved should be pleased with their efforts. This writer urges readers to not only attend this show, but to continue to support the diverse independent theatre productions throughout Sydney.