Walking out of Winyanboga Yurringa, it’s hard not to be taken aback by its sheer scope and ambition.

Directed by Anthea Williams, Belvoir’s latest offering is a production with a kaleidoscopic palette of themes and goals, ranging from coming-of-age tale to inter-generational rekindling to biting critique of the bourgeois art museum world. Yet, it’s the pursuit of this expansiveness that often feels like the play’s biggest inconsistency; the spaces for further depth clearly acknowledged but left disappointingly unfilled.

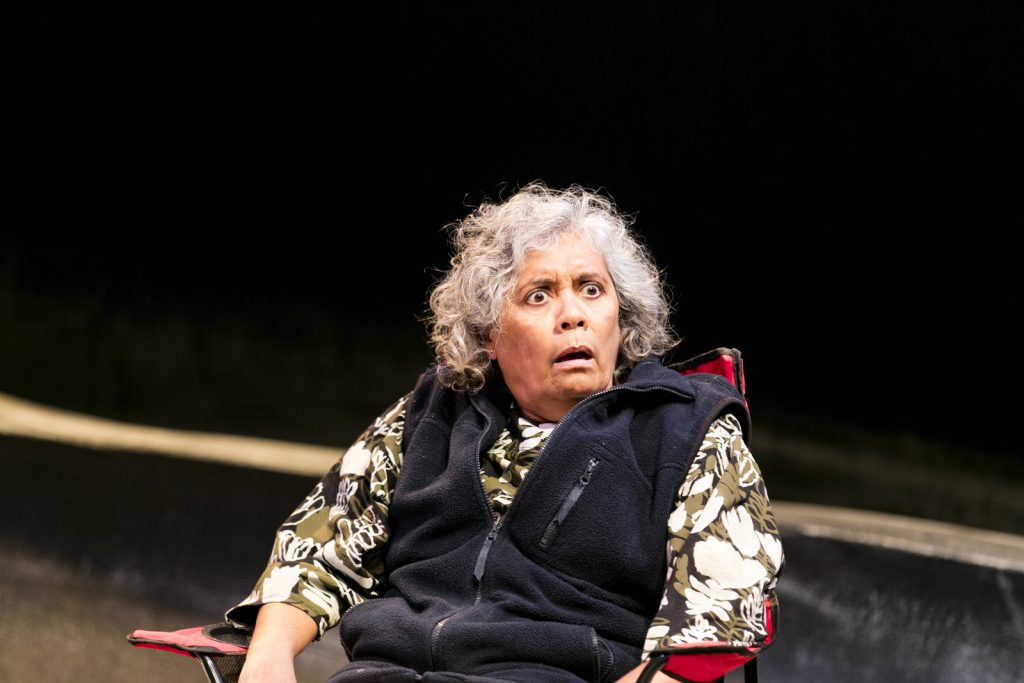

The play opens with an alluringly simple premise: three generations of Indigenous women have returned to a site in the Australian countryside sacred to their family, and a discord of age and culture triggers chaos almost immediately. Neecy (Roxanne McDonald) is the wise matriarch, who not only acts as peacekeeper between the outspoken voices of her daughters, but also as a spiritual guide in reawakening their connection to the land. The trio of sisters Wanda (Angeline Penrith), Carol (Tasma Walton) and Margie (Dalara Williams) each represent distinct, starkly contrasting intersections of Australia’s middle-aged Indigenous women. The chemistry between these siblings is volatile and electric, always on the edge of heated debate but more often than not in wistful reflection.

The voice of the youth is captured in Chantelle (Dubs Yunupingu), a Facebook-obsessed teenager who, despite the lofty aims of her seniors, wants only to find some internet reception so that she can text her boyfriend. Chantelle acts as a counterpoint to the rest of the cast – a naïve but combative member who dips in and out of conversation, underscoring the inter-generational differences of the cast.

Real sparks begin to fly when Jadah (Tulli Narkle), a pale-skinned photographer, arrives on the scene unexpected, catalysing some of the play’s most interesting discourses. Questions of conflicted identity, cultural theft and sexuality comprise most of the play’s runtime, broaching domestic violence and post-colonial reclamation in its latter half. While the production has some breathtaking set pieces – a confrontation between Jadah and Wanda stands out in mind – my reaction to Andrea James’ multi-faceted script, and the actresses’ interpretations of such, is ultimately one of yearning.

The narrative’s more polemical moments, such as its self-aware critique of fine art culture, always seems to shy just short of revelatory; I found myself desperately urging the writing to go a little further or dig a little deeper to expose the hypocrisies it was trying to uncover. At other times, character subtlety is abandoned in favour of advancing the story or squeezing some laughs from the audience, resulting in performances that feel forced and awkward: one particular scene sees civil conversation degrade into screaming existential crisis in the space of a few lines. Finally, the humour is consistently hit-or-miss, with some of Chantelle’s angst-filled quips a little too ‘fellow kids’ to be taken seriously. I mean, are we still meant to find selfie jokes funny in 2019?

From a technical standpoint, however, I was far more impressed. The stunning lighting design, crafted by Verity Hampson and Chloe Ogilvie, transforms the relatively small Belvoir theatre space into an expansive and atmospheric vision of the land. In understated scenes, it establishes a naturalistic and welcoming environment; in moments of crisis, the entire set pulsates with surreal, overwhelming colour. The sound design, consisting of gentle cricket clicks, the gentle hum of a nearby river, and sparse strums of acoustic guitar was wonderfully ambient and engrossing – credit to Steve Francis and Brendon Boney for establishing such a compelling sound-space!

All in all, it’s hard to fault Winyanboga Yurringa outside of some prominent issues with its writing. Though it’s a play with inspiring ambitions, a powerful all-female cast and a sublime set, I can’t help but imagine what it could have been if it had a little more focus and conviction with its strongest arguments.